By Josh Cosford, Contributing Editor

Let’s start by stating the obvious: seal geometries matter, or the fluid power realm would use only geometrically simple O-rings. The other two critical factors for effective seal performance are polymer composition and a machined groove to call home. However, even considering the latter, a seal geometry of the same material in the same pocket can have vastly different performance curves.

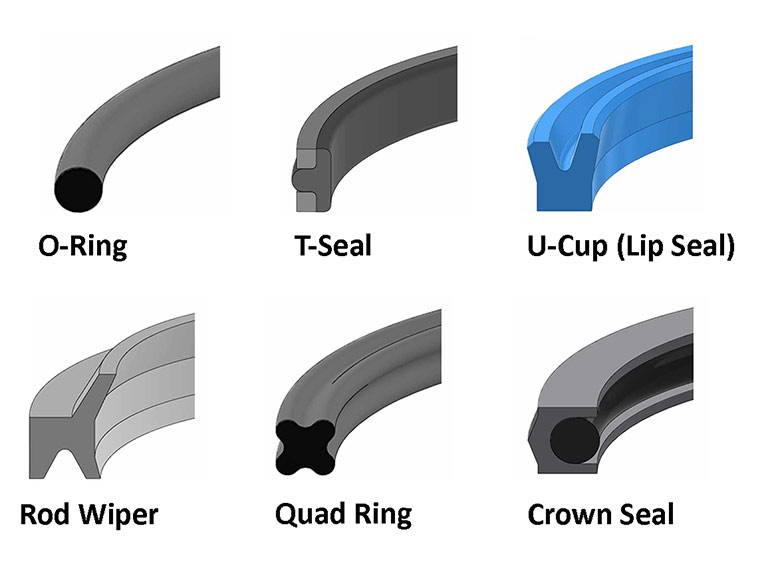

Much of a seal geometry is described by its cross-sectional shape, and for the most part, that’s what this article will cover. There are some relatively obsolete technologies, such as the V-Packing or Chevron Seals, which were stacked front to back and compressed with a retainer. I’m going to cover the most popular seal cross sections (Figure 1) and ignore the material composition.

The O-ring is fairly self-explanatory and is a basic seal with a circular cross-section. These seals are meant to take the shape of their groove and work best as static (stationary) seals. They are also designed frequently as an interference fit, meaning they are diametrically larger than the component they are sealing. For example, if used to seal a bearing or gland against the head of a hydraulic cylinder, the O-ring may be a couple of thousandths of an inch larger than the ID of the head, ensuring a positive seal.

When O-rings are used dynamically, there is potential for the friction of movement to push the seal through the extrusion gap, especially as pressure rises. The extrusion gap is the clearance between the two sealed parts, such as the piston and barrel of an air or hydraulic cylinder. Adding thin, rectangular backup rings to either side of the O-ring provides extrusion resistance. Better yet, the T-seal (the T is upside down) provides a compound shape with two backup rings that snap into place for superior alignment. T-seals are quite effective for positive sealing, although they are poor for high-velocity or responsive cylinders.

The next most common shape is the U-cup, also known simply as lip seals. Laying with the heel down, these resemble a U-shape and are superior for high-velocity applications or those requiring low breakaway force (the pressure is required to overcome static friction and begin moving). Even with low breakaway, the U-cup is great for high-pressure applications. The “lips” of the seal are acted upon and energized relative to pressure, so their low initial friction is not a detriment to pressure capacity.

U-cups and lip seals are used on both pistons and rods, but rods also have a unique requirement, nothing directly related to sealing air and oil. A rod wiper is unique in that its function is to remove contamination from the rod as it retracts, preventing grime, dirt and fallout from being pulled into the cylinder body. The seal comes in many forms, but for light-duty applications, they are also offered in combination with a rod seal. This cross-section could replace a standard rod seal and rod wiper combination or be used in conjunction with a typical rod U-cup for extra sealing protection.

The geometry available for air and hydraulic seals is expansive, to say the least. It would be impossible to describe all the options, although there are a couple more worthy of honorable mention. The “quad ring” is a take on the O-ring design that uses what appears as four O-rings resembling the shape of a four-leaf clover. Its four lobes provide superior extrusion resistance and twice the sealing surface as an O-ring.

The last seal geometry to cover is the specialized piston seal. Although U-cups are great for dynamic applications, they do tend to allow a bit of leakage, and O-rings or T-seals tend to penalize positive sealing with high friction and low velocity. The specialized “piston seal” is a generic term for any given manufacturer’s take on sealing a piston. The crown seal is one such design, which uses a special compound shape energized by a large O-ring. This design allows for both high-pressure sealing and respectable breakaway and velocity performance.

Seal geometry continues to advance, and the incremental changes offered to seal designs provide options not previously enjoyed by simple shapes. The ideal geometry is one that provides superior pressure capacity, low friction and responsive breakaway. Regardless of material composition, research the latest in seal technology to find a geometry that works best in your application.

Leave a Reply